This blog has now moved.

Please see https://www.allankellyassociates.co.uk/blog/

Hopefully your browser will automatically redirect there - and all the old links will work.

Thanks Blogger for 12 good years!

This blog is now at: https://www.allankelly.net/blog/ You should be redirected shortly. If you have any problems with it please let me know.

This blog has now moved.

Please see https://www.allankellyassociates.co.uk/blog/

Hopefully your browser will automatically redirect there - and all the old links will work.

Thanks Blogger for 12 good years!

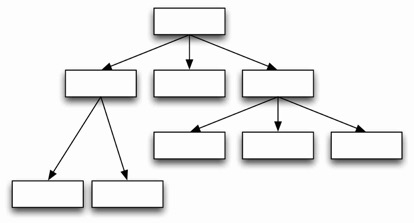

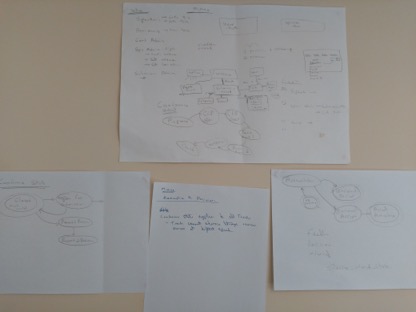

The picture above, I recently added this picture to Continuous Digital for a discussion of teams. When you look at it…

Over 10 years on Blogger, I’m now merging my blog into a new site, you can read the rest of this post at www.allankelly.net - the new site is still under construction but will merge the blog, allankelly.net and SoftwareStrategy.co.uk (my commercial entity) into one.

“Some readers have found it curious that The Mythical Man Month devotes most of the essays to the managerial aspects of software engineering, rather than the many technical issues. This bias ... sprang from [my] conviction that the quality of the people on a project, and their organization and management, are much more important factors in the success than are the tools they use or the technical approaches they take.” Frederick P. Brooks, The Mythical Man Month - Anniversary Edition (1995a, p.276)

This is one of my favourite quotes about software development.

Those of you who followed my management mini-series last year might remember some of my conclusions, specifically:

I can’t remember if I said it in that series or in another post: the quality of management in software development is often poor.

So now I’m going to do something about it.

Part of the problem is that very very few software engineers ever take time to learn about management. Sure they learn about Java, BDD, AWS, CSS etc. etc. but most people learn “managing” by watching the people who had the job before them. Unfortunately that tends to propagate poor management.

Why don’t people take the time to learn management skills the way they do technical skills?

A few days in the classroom learning about Java is great, why not spend a little time learning about management?

Now most readers probably know that I provide training, usually agile training to teams, but I have long felt that simply offering a two day training course for current and future managers wouldn’t be enough. I’ve long dreamt of offering a course that ran over a series of weeks, that allowed people to mix classroom learning and discussion of topics with hands on practice and, perhaps more importantly, reflection and group discussion.

Now I’m partnering up with Learning Connexions to offer just this course - I’m more excited about this than anything I have been in a while!

It’s going to run this autumn, September to December, half a day every two weeks.

In each session I’ll present some material but more importantly we’ll have discussions between people doing work. We’ll try and apply the material to real work. I expect group discussions will go beyond the stated subjects and allow everyone - me included! - to learn from one another.

Not only is this a new course it is a new way of approaching learning in work. Since it is new the course we are going to keep the price down. We’re running it on Friday afternoons so hopefully it won’t interfere with the usual work week too much.

Here are the hypothesis I’m testing:

The hypothesis you would be testing by coming along are:

I hope, I very much hope we can make this work…. - please get over to Learning Connexions and book Leading & Managing Agile today. Even if you cannot attend I’d love to know your thoughts on this, please give me feedback - comment here or mail me direct, allan@allankelly.net.

And apologies, I’m going to be talking more about this in the next few weeks as I put material together and get more and more excited!

My last blog, “Creating Beautiful Roadmaps - NOT!”, highlighted how the term “roadmap” is used and abused. While I’m probably in the minority in seeing a roadmap as long range scenario planning exercises to enhance learning there isn’t really a consensus on what a roadmap is…

To some a roadmap is a plan of how a product will evolve in the next few years. To others a roadmap is a set of promises with dates made to customers, higher management and others. Most of the roadmaps I see are little more than bucket lists with dates, fantasy dates at that.

Increasingly “roadmap” is used to describe a “release plan”, that is, a list of release dates and for each date a list of features that will be included in that release. Since these are usually based on estimates they are doomed to failure because very few teams can produce meaningful estimates.

Release plans made sense when releases were occasional, say every quarter but once they became fortnightly they loose logic. What is the point of planning releases if you release when the feature is ready? Many times a day?

So imaging how my heart sank a few weeks ago when a client said: “And I’d like you to run a road mapping session for the team next week.”

Worse still, there was no escape, I was visiting a client in Australia, I suddenly wondered if I’d done the right thing flying around the world!

So although I smiled and nodded inside I thought “Bugger!”

A day or two later I enquired about expectations, what did they hope to get from this exercise? Fortunately the answer was “An understanding of what the team will be doing in the next six months.”

OK, this wasn’t a full blown scenario planning exercise it was a mid-range scheduling plan. Normally I see little point in scheduling more than three months in advance - at most! Since this team was changing their work processes, personnel had been in a state of flux and there was no historical data this was going to be difficult.

My next stop was the Product Owner. He had a long list of things the customers - internal and external - wanted. Most of these were little more than headlines and they were all a long way from stories or epics so there was little to go on. The sheer quantity of ideas was so long that saying “No” and deciding what ideas not to work on was clearly going to be essential.

Given the vagueness and unreliability of inputs one could be forgiven for despairing but instead I saw opportunity. The problem was not so much one of road mapping or scheduling but deciding how the team were to divide their time up for the next six months. This was more big ticket prioritisation.

The vagueness of the requirements and specifications meant that once the time was divided up the team would mostly have a free hand in deciding what needed to be done and what they could do in the time allowed.

Without performance data there was no way estimation could be a reliable guide so there was no point in even thinking about it. But if one was to try estimation one would need something to estimate, which means the requirements would need fleshing out and with so many possible options that would be a lot of work. Not only did we not have the time to do such work but since we knew some items would not make the cut fleshing them out, let alone estimating them, was work which would be wasted.

Just as this was looking like mission impossible I remembered Chris Matts Capacity Planning approach. The roadmap request was actually a capacity planning exercise. Chris’ approach would need a few tweaks but it might just work…

In Chris’ version the product owners estimated the work. At first this sounds awful, product people estimating how long technical work will take! Help!

While Chris says this I’ve never seen these “estimates” as real effort estimates. I’ve always viewed them as “bids.” Each product owner wants to get as much time as they can for their chosen work. But they also know that the higher their bid the less likely they are to get what they ask for. So in “estimating” they are both bidding and self-limiting. Once they have a work allocation they will have to adjust what they ask for to get it into the time.

Rather than ask the product folk to estimate or bid I decided to ask them how many nominal days they would like to allot to each item. How would they divide the capacity between competing requests?

Secondly I decided to ask them to order request items. Thus, a line item could have a very high allocation of time but be late in the scheduling order; conversely a small effort item could be high up the priority list.

So…

The first task was to knock the wish list into shape as a series of line items.

For each line item we gave a short description and statement of anticipated benefits in a spreadsheet. Each item had a box for “days” and “order.”

Next we took a stab at calculating how many days team P had: six months for 10 people equated to approximately 1280 working days.

My plan was to have each manager allocate 1280 between the line items and assign each item a priority position. Then we would average the numbers and use the combined result as the basis of a discussion before finalising the allocations. Finally we would turn the allocated days into percentages and hand them to the team together with the priority order.

So far, so good. The meeting commenced: three managers, three techies, one team product owner and me. (Only the managers got to vote.)

To my surprise the managers readily accepted the approach: I had feared they would want detail on the line items and effort estimates.

While I had intended to hand out the printed spreadsheet, collect the numbers and average them someone decided we should put them on screen. So the whole spreadsheet was projected on screen and it became a collective exercise.

Very quickly about half the items were dismissed and allocated zero time. They were all good ideas but given capacity constrains they clearly weren’t going to win any time.

Some of the remaining items were split up and others combined. Before hand I had worried whether we had the right granularity and even the right items but the group quickly addressed such concerns without me needing to mention them.

(Anyway, I didn’t want fine granularity because that would hinder the teams ability to decide what it wanted to do.)

Next each line item was discussed and assigned an order. I had intended to order them into strict 1, 2, 3, …. but these quickly became buckets, there were several #1 items, several #2 and finally some #3.

With the “order buckets” decided we moved onto allocating nominal days. We quickly decided to simply work with 1,000 nominal days. I quickly calculated how many points equated to one developer for one sprint, how many points equalled the whole team for one sprint and a couple of other reference points to help guide the process.

The days were allocated - including an allowance for technical investment - and we were at 1300 nominal days committed, 300 over budget. Now things got hard so we stopped for lunch.

After lunch I expected a fight. But I knew that if the worst happened when we converted to percentages everything would be cut by 30%. Moving to percentages would force any cuts the meeting couldn’t make.

Maybe it was the effect of lunch but these hard decisions were taken quickly, to my immense surprise. The managers concerned could easily see the situation. Once the capacity constrain and work requests were clear the competition became clear too.

Most of all I had succeeded in preventing managers from arguing over who was doing what. There was no attempt to say “Peter will do X and Fred will do Y.” The team had a free hand to decide how to organise themselves to meet the managers’ priorities.

I was delighted with the way the whole exercise went, having tried capacity planning once I expect I’ll be doing it again - I may even build it into some of my training courses!

What do you think? Anyone else done this? - please leave me a note in the comments

Subject: Create Beautiful Roadmaps in Minutes

Body:

Hi << Test Name >>,

I hope you enjoyed reading our guide to product roadmaps.

If you haven't already built a roadmap in _____, I'd encourage you sign up for a free trial.

Why did this email annoy me so? - apart from the failed name substitution that is.

This e-mail, perhaps spam or perhaps something I did sign up to, landed in my e-mail box the other day and set my blood boiling.

Roadmaps should most definitely NOT be created in minutes. Roadmap should take time, roadmaps should take lots of people’s time.

The value of roadmaps is not in what they say. There is a lot of value in what they don’t say - the things that the organization will not do. But the real value of the roadmap is in the creation of the roadmaps.

The act of creating the roadmap brings key people together and exposes them information about the future.

Peter Drucker once said: “We have no facts about the future” but there are probabilities: population changes is one that can be accurately predicted years ahead (e.g. we know how many 20 year olds there will be in 10 years time.) Most legal changes can be seen coming at least a few months out. There are things we can take a view on, there are things we know we don’t know, and things were we need to keep options open.

When key people are brought together they can exchange information and views. They can share their views of the future, they can talk about how they see the future, they can build a shared model and out of these can come a possible future, a possible scenario, a roadmap, which shows how your product will add value to some customers.

Because that’s what a roadmap is: a scenario plan, one or more possible descriptions of the future for your product.

Like so much planning it is the exercise of creating the plan that is the valuable bit rather than the resulting plan itself. This is especially true for roadmaps which are attempting to look far into the future. Roadmaps need to be a mix of prediction and opinion.

Roadmaps should bring people together for a discussion, to hear each others voice and opinion, creating the roadmap should be discussion.

Reducing roadmaps to a few minutes work with a tool destroys the value of the exercise. Any organization that does this has a pretty screwed up idea of collaboration.

Next time you need to create a roadmap:

And repeat the process regularly, say every six months.

You might even build several scenarios about the future and consider the implications for your product in each. Such scenario roadmaps are there to shape peoples view of the future. Your scenarios will probably be wrong and the roadmap will play out differently in the end but allowing people to consider alternative futures challenges them to think differently. When real events happen the fact that people have considered alternatives will mean they are better prepared - even though the future will be different to all your scenarios!

(Museums of the future, future memories, retrospectives and change is a blog post about future memories from 10 years back.)

If you are a regular reader of this blog and you’ve not had a chance to check-out Continuous Digital (aka #NoProjects) then I recommend you do! - but then I would say that wouldn’t I? :)

I’ve set up a discount coupon so readers can get Continuous Digital for $5 (plus any tax your Government my levy on ebooks.)

Now is a good time to start reading Continuous Digital because the content is done, my arguments are made. From here on I expect its all refinement - debugging. I need to do an end-to-end edit to make it internal consistent and then I need to get it copy edited. (Again as regular readers will know, grammar, spelling and such isn’t my strong point - and it never will be!)

I’m going to add an appreciation page - thats a page were people say nice things about the book. So I’m on the lookout for appreciations, if you have something nice to say about the book please drop me a note and I’ll include your name with your quote.

When does empathy become Stockholm syndrome?

“Stockholm syndrome is a condition that causes hostages to develop a psychological alliance with their captors as a survival strategy during captivity. These feelings, resulting from a bond formed between captor and captives during intimate time spent together, are generally considered irrational in light of the danger or risk endured by the victims. Generally speaking, Stockholm syndrome consists of ‘strong emotional ties that develop between two persons where one person intermittently harasses, beats, threatens, abuses, or intimidates the other.’” Wikipedia

It is one thing to have empathy with someone else’s outlook but sometimes empath gives way to something stronger, too much empathy not only becomes self-limiting but damaging to oneself.

Sometime when I argue the case for improving software quality - reducing defects, increasing maintainability - programmers start by telling me that their managers don’t care about quality. I talk about the cost and time implications of poor quality, and again I’m told that manager value speed above all else.

Asked who is to blame they point the finger at faceless “managers” who will not allow quality, will not allow the right design, tests, refactoring or anything else which is “good.” Ask what should be done to improve it and they will say “We don’t have time.”

Very, very, often I find myself debating with professional engineers who simultaneously despair at the lack of quality built into their code but claim that the company cannot afford quality. (See my old post The quick and dirty myth.)

Frankly, I think some programmers and testers suffer from a version of Stockholm syndrome: they simultaneously blame others but take on those views themselves.

Maybe it is not Stockholm syndrome, maybe its just a failure to take responsibility.

I actually find it easier to convince managers of the advantages of automated testing and test-first development. I find managers understand that higher quality is faster and cheaper when it is explained to them. I find managers are open to the argument that it is better to do less and do it better quality.

It seems to me that some unreformed managers do hold these opinions and they may well voice the need for speed to programmers. A few might even suggest that testing can be skipped.

But, since when was the manager the expert in the way to develop program code? Managers are managers not design experts, surely that is the programmers job? Many managers know they are not code experts, they know the programmers are.

Of course managers - and other “business” people want results faster - don’t we all? And of course they are focused on what customers want. Is there something wrong with that?

Managers are often in a worse position that programmers and testers because they are answerable to their own managers but lack the ability to do programming work. They are reduced to the position of children in the back of the car asking “Are we there yet?”

Overtime programmers come to share the same desire for speed, the same need to showing something. But since programmers control the means of production they take action, they make compromises with themselves. They cut quality. They skimp testing - after all their own code won’t contain defects. They abuse interfaces, they drop tests, increase coupling and reduce cohesion, avoid refactoring, they live with broken tests and they tell themselves “we can fix it later” even if everyone knows. (Not going back and fixing the things they meant to fix is another example of reducing quality.)

Time and time again I meet developers who do these things and claim “my manager won’t let me”. And I ask inside my head: “Does the manager sit beside them and tell them not to do these things?”

I’ve known managers who have said: “Ship bugs” but I’ve known more managers who haven’t said that.

The view that quality needs to be dropped seems to have two sources: ignorant managers and unprofessional managers who demand shoddy work, and, secondly, programmers who assume a desire for speed is a request to drop quality.

Sometimes I challenge programmers to tell me which managers have voiced the “reduce quality” argument. More often than not they cannot name such a manager. It is the programmers who interpret the managers - understandable desire - for speed as a request to cut quality.

I suspect that having cut corners and reduced quality programmers feel guilt. And that guilt leads them to make assumptions - perhaps even invent false memories - which allow them to pass these failings onto their manager.

I’m not saying managers are perfect or blameless. I am saying I think many programmers are more responsible for problems than they care to accept. (And of course, some just don’t know any better.)

In my mind programmers are engineers; engineers create solutions within constraints and professionalism should guild them to do the best job they can within those constraints.

Managers are like kids in the back seat of a car, if you keep giving them chocolate and telling them you are almost there they will expect more chocolate and to arrive soon. When you stop giving them chocolate and carry on driving is it any surprise they get upset?

Image: Gamla Stan stop in Stockholm by Kabelleger CCL on WikiCommons.

A big part of Agile is about giving the workers, or rather the team, authority to do their job - putting people into control of their own work. Many people talk about self-organizing and self-managing teams, I prefer to talk about distributing and devolving authority but its all about the same thing.

I recently stumbled across an article discussing an initiative at Michelin called responsabilisation giving factories and workers more authority with responsibility. This French word, responsabilisation, deserves adopting by the Agile community.

What ever we call it, it is:

Again and again I find that electronic work management and tracking tools get in the way of doing this. Electronic tracking tools, of which Jira is the best known, disempower workers and give power, and control, to the tool and those who control the tool.

For example, typically in a planning meeting one person will “drive” Jira. That one person has a keyboard and mouse and controls the screen. They decide what is displayed and they get to create new items, drag existing ones around and ultimately decide what is done.

The others, the rest of the team, sit facing the screen and sometimes at the Jira driver. The driver has power, the driver becomes the manager of the meeting. Rather than interact with each other they interact with the driver and the machine.

Conversely, in a similar meeting using paper and cards someone may well have authority over the cards but they can be moved by anyone. New cards can be written by anyone. People focus on the work and on each other. The conversation isn’t moderated by the Jira driver - it moves.

The Jira driver has power, they have control.

And it is not just in the meeting.

In Jira - and similar tools - someone has to set the tool up, someone has to decide board layout, someone granters access permissions, everyone has a “role” in the software, they are defined by their role.

The Jira admin has power and control.

In the worst cases teams have little power to change Jira because the organization mandates they must set it up like other teams. Again, the organization holds power back.

And since Jira controls the workflow, Jira controls the to-do list, Jira controls the reporting… he who control Jira controls the work.

Jira is not alone in this respect. All electronic tools exhibit this problem. Jira is possibly worse than some because the interface is very complex and acts as an additional barrier to worker involvement.

Tools built on and around Jira make this worse. Supplementing Jira with additional tools makes Jira more powerful and that makes the Jira admins and drivers more powerful.

While Jira produces a mass of reports most people don’t understand or use them. Worse still are those who use the reporting mechanism to forecast delivery dates into the future, because these come from a tool they perpetuate the illusion of certainty.

Electronic tools reimpose the power structures, illusions and control that the Agile movement set out to remove.

Someone asked me this the other day: “Why do devs hate agile?” and as I worked through my answer I thought it worth writing down. There are three reasons I can think of but before we get to them…

First off, I don’t think all “devs do hate Agile”. Or rather, I don’t think the vast majority of them hate it - and hate is a very strong word. Sure some do, no doubt but all? A blanket “all devs hate” ? No.

I do think its is fashionable to slag agile off, and few do this better than the agile community themselves. And unfortunately like a lot of fashions once it gets started it catches on. Once dev A says “I hate Agile” then dev B thinks its cool to say it too, and dev C sees A and B doing it so joins in.

The ironic thing about all this is that Agile is the product of developers. In the beginning it was developers - like me - who saw that the classical way of doing things (write down what the customer wants, design it, plan it, code, it, etc.) didn’t work very well but noticed that the way most work actually happens (quick, code foo… O foo is not quite right change it, quick) was actually better.

I was inspired by Jim McCathy’s book Dynamics of Software Development. Jim was a developer, albeit a developer who had started managing other developers. It was that book that made me think “alternative ways are valid.”

Similar insights were occurring with developers all over the world - as they raced to fix Y2K using heavy weight processes. Some of these coders went on to become mildly famous: Kent Beck, Ward Cunningham and Martin Fowler for example.

And here in lies number #1 why “devs hate agile.”

Theft and imposition.

Agile was all about dev in the early days - especially XP. Just 10 years ago coders would say “I’d love to work Agile by my (project) manager won’t let me.” So we set about making Agile manager friendly, we expanded the business arguments for why Agile was good, and managers got it. Now you hear developers saying things like “My manager wants me to work agile but he doesn’t understand” or “My manager wants me to work agile but does’t help.”

In the beginning Agile was a bottom up movement. Now it is a top-down movement, change is imposed on people rather than people wanting to change.

That is wrong.

Making it worse is the fact that many of those imposing the change frequently fail to understand the change they are imposing or do not question their own thinking. Management thinking needs to change too - start with Software Development is Upside Down.

Reason #1: Agile is now an imposed change.

In my experience developers want to work Agile because true Agile allows them - no, demands - they do a quality job. Agile doesn’t deliver half the benefits it promises if organizations don’t pay attention to quality, that means their technical practices, thats what we used to call technical excellence. That means developers doing work that are proud of.

Namely “technical practices from XP”, specifically: simple design, relentless refactoring, test driven development (plus behaviour driven development), pair programming and things like face-to-face conversations and “story is a placeholder for a conversation.”

I’ll point the finger specifically at Scrum, and later Kanban, for not mandating these practices - something I did with Xanpan. Part of making agile acceptable to management was removing the words extreme and programming, and down playing the difference high quality can make.

Without these practices teams are driven harder to deliver something sooner and quality drops. As quality drops it gets more difficult to deliver anything in a short amount of time. Consequently more is demanded of coders, stress and tension rise and it is not fun.

Reason #2: Agile without technical quality makes developers lives worse.

I remember meeting some coders in Cambridge, almost the first thing they told me was “We hate Agile, our managers went on a Scrum course and have insisted we do it for months.” I quickly discovered that they were not doing any technical practices, as a result they were racking up more and more technical liabilities and making their own lives harder. Once I explained that they were missing the technical practices their attitude changed.

Now to the final reason, perhaps the big reason…

The Agile toolset is intended to help teams organize themselves, it is intended to make problems visible so they can be addressed and fixed. In the hands of people with the right attitude this is brilliant.

Teams don’t need a manager (although one may still be useful).

Teams can see problems.

And teams can fix problems.

But… the very same tools used by someone with the wrong attitude are a micro-managers dream.

Which micro-managers wouldn’t want everyone to give a status report at 9.00am every day?

Who wouldn’t want to see all work broken down to pieces for which NAMED individuals could be held accountable?

And why wouldn’t they want to make a shocked face and send a very clear “that is not acceptable” message every time an estimate was high?

Visibility becomes a tool of blame.

I once helped a team at an airline set up a Kanban board, instead of using it to see bottlenecks, problems and find opportunities to improve the managers concerned used it to assign blame, point fingers and demonstrate that nothing was happening because someone else wasn’t doing their job.

Reason #3: In the wrong hands the same Agile tools are very effective micromanagement tools.

An old product manager friend writes….

“Just started a new gig as senior product manager at blah blah blah

Discovering that scrum teams aren't organized around products but rather engineering components. For instance a product manager has to work with three different scrum teams:

- front end

- back end

- data science

This makes it hard for Product Managers to manage but I assume easier for engineering. I've not encountered this before. Thoughts?

At any given scrum meeting there may be two or more product managers, as opposed to a single product manager per scrum team.”

OK lets see…

The organization is horizontally organised, not good - we’re back to Conway’s Law. Getting anything of business value delivered is probably going to entail getting the front end team to do something, the back-end team to do something else, and then the data science team to do something…

Now it is possible that that is the way the work falls. Its just possible that a lot of the work falls inside one component, e.g. data science, and that alone delivers business benefit. If the majority of the work is like that then horizontal organization makes sense.

But, in my experience that is rarely the case, and your comments suggest this is true here too.

Think of it in user story terms: stories rarely relate to one function, you are far more likely to need a little bit from each functional team. No one team can complete a whole story, they need the other teams to do something.

This makes work for project manager types to do - has team A done their bit so team B can start and why aren’t team C talking to team A?

The approach normally advocated by agile folks is Vertical teams.

Each team should be staffed to delivered business value itself: if it needs a representative from each function then so be it, if team members need more training, or need permission to go into a different part of the code then make it so.

Horizontal organization is’t that uncommon, it is usually adopted on the grounds that you need specialists and specialists need to focus on one thing. While you may still need specialists you want people to cross boundaries and do be business priority driven.

Then there is the question of product managers and product owners, o not again…

In this context the product managers ARE the product owners. Pick up the Scrum book, replace every instance of “product owner” with “product manager” and things are clearer.

And it is OK to have multiple product people in the scrum meeting - by the way, when you say “Scrum Meeting” do you mean “Stand up” or “Planning” meeting? Either way it doesn’t matter, you can have two Product people in each.

The important thing, especially if you mean the planning meeting, is: the product people speak with one voice.

Perhaps they have a common backlog.

Perhaps they have a pre-planning meeting of their own to decide priorities.

Perhaps they divide the work up as Strategic Product Owner/Manager and Tactical Product Owner/Manager.

Perhaps they agree one looks at segment X and the other looks at segment Y and they compare notes.

However they do it they need to speak with one voice. They need to agree.

A more interesting question is: why do you even have two?

Do each focus on different markets? Different aspects of the product? Or different time-frames?

It is entirely possible that if you had two vertical teams instead of three horizontal teams that one PM feeds one team and the other PM feeds the other team. In between times they both get out and see customers and decide between themselves what the longer term strategy, tactics and plans are.

If you want to annoy me say something like “Building software should be like building a house…”. To say I’m not a fan of physical building metaphors is something of an understatement, but… I think I may have notice something.

Take that picture above, no they are not space rockets, they are swords.

The Sunday morning, for the first time in something over 35 years I engaged in making something out of wood, calling it carpentry is an extravagance, but my sons wants to do some sawing - and all boys should get to saw shouldn’t they?

Specifically they wanted some swords to play with, so out came the bench, out came the saw and… Not bad, I’m a real man! - I can make children’s toys!

Look closely at the swords and you will notice that down towards the handle they have a pair of “wings” - actually they are meant to be hand guards. This was a requirement I only discovered during construction when the older boy decided his should be different to the younger boy’s.

So yes, requirements change and expand when you build real things too. Especially when innovation and differentiation are in play.

When he asked for this I had no idea how I was going to do this. Rather than stop and work it out I thought “umm… maybe he’ll forget, maybe I’ll think of something” - and carried on working.

I did think of something, I realised that if I used the offcuts from the top I could create the desired effect. Now here is the lesson.

Constructing the first sword took about 20 minutes - without the “wings”. The second sword took less time, maybe 10 minutes - again without the “wings” - because I knew what I was doing.

The process went surprisingly smoothly and I discovered I remembered a lot of both my school woodwork and time in the garage with my own Dad.

But, then I started on the “wings”.

These small additions took the same amount of time again, perhaps even longer. I also got into a mess with nails, screws and ended up using wood glue. The beautiful smooth finish is now broken by a protruding nail.

Put this in software terms: it took less than half the total time to constructing the two basic products, building the infrastructure went smoothly. It was the additions and “nice to haves” - or rather the innovations - that took up most of the time and caused the greatest problems.

Last autumn I had builders in change my house. In the first three weeks the basic product was created: a physical wall was taken out, an external door bricked up, a window moved and the floor, electrics and plumbing ripped out. All the heavy lifting was done quite quickly.

Things slowed down, it took another three weeks to construct a new internal closet and lay a new floor.

It then took another six weeks to finish the plumbing, electrics, finish off the construction, fit a kitchen and decorate it.

See? The heavy lifting, the bit most visible, the bit which actually requires physical work is done quite quickly. It is the detailed work which goes slowly, probably because it requires attention to detail.

It was damn frustrating: the hard bit was done, the wall was gone, a steel beam installed, why wasn’t everything else just done? Maybe I should speak to the main guy and say “can we get more people in?” or “can’t we work in parallel now?”

Isn’t this like software?

I got Mimas up and running in a week or two but it took me another couple of months to get all the ins-and-outs working the way I wanted them too.

You can install a WordPress site, even with Magento, in half a day. But getting it styled right takes weeks.

You can build a rough bare bones app in a few days. But doing all the detail takes months.

And many efforts are so scared of heavy lifting the try to project manage it away and the project management becomes more than the real work.

The problem is: to those who are not doing the work - my kids watching me, me watching the builders, your customers watching you - the bit they expect to take time - the heavy lifting - is actually quick. It is the detail that is slow.

Writing this now it occurs to me that this is exact what happens with ERP systems. SAP, Microsoft and Oracle come along, install the basic ERP and it is there in a matter of days - hurray, all the hard work done! Just detail, mere “configuration” left to do. Except the configuration is detail and detail takes time.

Its also true of blogs. Blogs like this I can bang in a few minutes. I take far longer editing them.

Once again the world is upside down.

Regular readers will be familiar with my rants against projects and my posts about NoProjects - if not you have a lot of catching up to do: NoProjects Q&A, Beyond #NoProjects, the podcast with Tom Cagley, presentations and lots more. And as many readers will know I’ve been working on a #NoProjects book on Leanpub.

The book will soon reach a point where the content is there, code-complete if you like. (Yes there are some batch process and debugging todo, another story.) The book has reached a point where it has outgrown the #NoProjects moniker and needs a new name. The new name is: Continuous Digital.

Before I explain the name change something special for readers: I’ve set up a discount on LeanPub for Blog readers. Continuous Digital is available for just $5 for this, the last week of April. Use that link or the code AprilBlog.

Now why the name change?

#NoProjects is a great rallying cry and accurately sums up my feeling that in many environments the cost and difficulty of project management actually makes things worse not better. Simply removing it and letting people do work would be a big improvement.

But #NoProjects is also absolute, confrontational and doesn’t actually say what one should do which is a pretty big flaw. An alternative needs a name which isn’t “No”.

#NoProjects has been a necessary step in this evolution, once you relax the mindset that says “everything is, or should be, a project” you see the world differently. This is more than just adopting a product model - although there is a lot of that.

What becomes immediately obvious is that the idea of “Projects” is itself a model - hence why I refer to “the project model”. And the project model is not the only way of managing. Indeed, project management has not always existed, there was a time before “projects” and there will be a time after “projects.” I see evidence all the time that companies are backing away from the project model.

Many of this things project advocates want are entirely possible in an alternative model: goals, estimates, new developments, portfolio management, governance and deadlines to name a few. One of my aims with the book has been to show how these ideas can still work in an alternative model.

The thing I come back to again and again is: successful software lives, it is used and continues to change. Projects, by definition, end. Success is continuous.

(I tried the name BeyondProjects for a while but it didn’t catch on and it got confused with things that go on top of the project model like portfolio management and governance. ProjectLess was another suggestion but “Less” is already overworked as the name of an agile scaling framework and as a CSS preprocessor.)

Now think for a minute, the word “digital” is all around us: “Software is eating the world”, almost all start-ups are software technology based, legacy corporations are rushing to embrace new ways of working and operating.

Yes this is about developing software but it is more. 30 years ago really only software companies developed software as their product. Today every business is, or soon will be, a software based business. Hence the word Digital.

We stand at a point in time where business is changing. The term “digital” tries to capture this change.

As more and more companies rush to embrace digital business it is vital they leave behind the idea that software is ever done.

In business world being done is bad: if you walk into you local Walmart, Tesco or Aldi and the shelves are empty and the manager says “Well we sold everything so we are closing” it is bad.

If Ford and Toyota turn around and say “Everyone who wants a car has one so we are closing” its bad.

Business thrives on change. If a business is digital then the change is going to be digital.

Digital business needs an alternative model to projects. A model that actually matches their business and does not pretend everything will be done one day.

Continuous Digital sets out that a model. Please buy and enjoy the book, its not finished (yet).

Can you have an epiphany more than once?

Well I did. In early January - perhaps the result of all the Christmas drink - I had an epiphany and wrote this blog post. As I finished writing the post I realised I’d said it all before… Something old, Something new:

Requirements and Specifications.

Still, I think the message is worth repeating…

Back in the early 1990’s everything was better, the Cold War had ended, the world seem be fighting just wars, I was having fun at University and my lectures were convinced that formal methods - logic based VDM-SL to be specific - were the silver bullet to software development. And so I spent three years being schooled to write pre and post-conditions on every function I wrote.

Actually, this made sense to me at the time and I continued it long into my professional career. I still find it useful to think like this although I long ago gave up actually writing them as comments. That was one of the failings, if you just wrote them as comments then they aren’t enforceable and they can easily become another piece of documentation which doesn’t match the code.

An improvement to this, and the way I used to write a lot of C++ code was to use assert. So my code would look something like this:

std::list<std::string>

extract_reviewers(std::map<std::string, int> *votes_cast) {

// pre

assert(votes_cast != null)

assert(!votes_cast.is_empty())

…

This was an improvement but you needed to execute the code to make it happen. And that meant powering up the whole system.

So today I’m writing some Python, and my app just crashed, and I looked at the code and its obvious that the function in question shouldn’t have been called. “Arh… there is a test I missed somewhere…”

And it dawned on me… probably again…

When I write a test for a function I’m writing executable pre and post conditions. Here is the code:

self.assertEquals(dedupvotes.retrieve_duplicate_report(self.c.key), None)report = dedupvotes.generate_duplicate_vote_report(self.c.key, 1)self.assertFalse(report.has_duplicates())voterecord.cast_new_vote(submission_keys[1], "Allan", 1, "One", VotingRound)voterecord.cast_new_vote(submission_keys[1], "Grisha", 2, "Two", VotingRound)self.assertFalse(report.has_duplicates())voterecord.cast_new_vote(submission_keys[1], "Allan", 1, "One", VotingRound)self.assertTrue(report.has_duplicates())

See?

In the test setup I setup the pre-conditions. I may even test them.

I call the function, generate_duplicate_vote_report, and I check what happens, the post conditions.

(OK, it is not the most polished code, the refactor step has yet to happen.)

What has happened here is that I’ve moved the policing of the pre and post conditions outside the function. In VDM the pre and posts were comments wrapped around some imaginary code. In C++ the asserts top-and-tailed the method, with TDD the pre-and-post it in a special function. And the test harness allows just that code to be tested.

I was always taught to write the pre and post conditions first. Indeed, in VDM there was no actual code so you could only write the pre and post conditions. In other words: I was writing the tests before the code.

And now I write this, I remember I have made the same point before. When I made this point before I was discussing TDD’s younger, but possibly wiser, brother, BDD. If you want to have a read it is Something old, Something new:

Requirements and Specifications. That essay is also included as an appendix to Little Book of Requirements and User Stories.

What does this prove?

Perhaps not a lot.

Or perhaps that TDD and BDD are the logical continuation of an old, 1970’s at least, approach. They have a longer lineage than is commonly recognised and that in turn increases their credibility.

It also reminds me of 1994 when I was working in the dungeon of a small company in Fulham. Myself and another programmer, Mark, were racing to deliver a C++ system to a client and save the company. We were writing test harnesses for our code and I was writing pre and post conditions. In retrospect his tests were better than mine, mine often needed a human key-press, I think his might have been added to the build to.

In retrospect too, we came perilously close to Test Driven Development but we didn’t think it was anything very special, we didn’t name it, we didn’t codify it and neither of use made much money out of it.

The last few years have been good to me, I’ve enjoyed giving advice to teams and companies and helping people get started with better ways of working, ways of working which usually go by the name of “agile” but the name is the least important thing. But…

I’ve been questioning if I want to keep doing this. Like most of us do from time to time I’ve wonder if I need new challenge, if I should join something big, more continuity and… as you might guess from my posts on Mimas I’ve kind of missed being closer to building something.

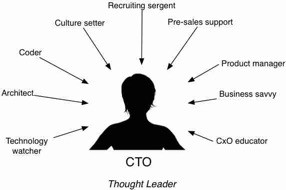

From time-to-time people have suggested I take on a CTO role - and certainly my ego likes the idea, it sounds important! - but, seriously, I think I’d like to give it a go. But that leads me to a question of my own:

Just what does a CTO do?

This is something I’ve pondered before because while I’ve met a good few CTOs in my time I can’t really see a consistent pattern to describe what they do. Everyone knows what a CFO does, they look after the money so a CTO should “look after” the technology but… how do you do that?

Before I come up with even more questions lets try some answers.

First up, lets be clear, not all CTOs are code-centric. I know organization where the primary role of the CTO is to understand the technology domain and code - software - is secondary. Take telecoms for example, the CTO in a telecoms company may actually be an expert in telecoms technology. Software may well be something someone else looks after, although the two need to work closely.

Such examples seem to becoming less and less common, perhaps that is just another example of software eating the world. CTOs are increasingly about the code…

Some CTOs are programmers, some CTOs are the only programmer.

This view seems common with non-technical entrepreneurs and in job-adverts for start-up companies. Maybe it is because these companies can’t afford to pay senior salaries that they hand out grand job titles instead. Or maybe it is because the founders really don’t understand technology and anyone who can code looks like a god to them.

I worry about these companies because the attributes which make the first “CTO” attractive (code god willing to work for peanuts and therefore young and mortgage free) are most definitely not the attributes you want a CTO as the company grows.

CTOs should most definitely be able to code - even if this was sometime in the past. And many CTOs I know, and have know, do continue to code. That is good when they are part of a team.

A CTO is also in part an architect role - and hence they should code from time to time. The CTO may well be the Chief Architect or Chief Engineer although such a role is more about building shared understanding not mandating plans.

And since software design is a copy of organizational design the CTO needs to understand Conway’s Law and organizational form and structure. Organizational architecture is as important as software architecture, they are symbiotic.

Some CTOs have a lot of say in organizational structure. Many CTOs run the technology development group - all the programmers and testers, and possibly analysts and project managers, report to the CTO. As such the CTO is the Chief Technology Manager.

But not all CTOs do this. Some CTOs are actually further down the organization. And some CTOs leave the running of the technology group to someone else - the Vice President of Engineering or Director of Development. Again the CTO may work closely with this person but the CTO fills more of an advisor or expert role rather than a management role.

Such expert CTOs may well be on the board, they may well have the ear of the CEO but they leave the day-to-day operation of development to someone else. And some don’t, some are deep in the detail.

Perhaps as more businesses become truly digital, and technology and business become truly one, then CTOs running development operations will become less common and CTOs as experts will become the norm.

CTOs need to keep their finger firmly on the pulse of technology - what is happening, whats new, what is taking off, what is going down, what are Apple planning? And Amazon? And Microsoft?

But actually understanding the latest technology may well be less important than understanding how that technology changes business, changes competition, changes organization and structure. Manager-CTOs may well put that understanding directly into action but Expert-CTOs will educate others in the organization, from new recruits all the way up to the board.

CTOs also have a role in recruitment and forming the development culture. If CTOs think quality is important the engineering staff will take quality seriously. And if the CTO says, like one I knew once, “I’d rather it was on time with bugs than late and working” then every engineer will know within about 5 minutes.

While CTOs may not interview every candidate for a role they will certainly interview some of the key roles. More importantly the CTOs needs to work as a cheer-leader for the companies recruitment campaigns. Finding good engineers is hard, a CTO who gives the company a profile and makes it a place people want to work will help a lot.

CTOs often have a role to play too in sales. They are wheeled out to meet potential customers, talk technology and show the company takes the client seriously. When a company is R&D heavy the CTO doesn’t do much pre-sales but then the company makes a living selling products or services to other companies CTO as pre-sales is very important.

And it is perhaps at the highest levels, the board, the other CxOs, that the CTO role is unique. Almost by definition each CxO (Chief something Officer) is a specialist in their own field: the CFO knows about finance and the CMO knows about marketing. Although the CEO should be more of a generalist they come from another function so once upon a time where specialists. The COO (operations) may be another exception although this is often post held by the soon-to-be-CEO so it is a training post. (In my experience, the CSO role (chief strategy officer), when it exists is used to sideline someone before helping them leave).

In the CTO the other CxOs have a peer they can talk about the technology implications for their business. It is here that the CTO has the opportunity to influence the rest of the company and help them maximise the benefit of technology.

The common theme in all of this is the CTO leads the thinking of others. To use a rather over-used, and perhaps equally vague term, the CTO is a thought leader around technology. The CTO helps others in the organization understand not so much the technology itself as the implications of technology for the business. (And that implies the CTO needs to be a good communicator.)

That of course is provided the CTO has those opportunities, that they are at meetings and senior meetings, if “CTO” is simply a grand title for a programmer then they have little influence.

Summary

Given that it is pretty obvious that very few, if any, individuals can fill the role. Any CTO will inevitably be good at some things and not so good at others, as humans they will inevitably flawed.

And me?

Do I still want to be an CTO? - well yes but actually, I’m not concerned about the title, call me what you will - Chief Engineer is a title I’d love too - but what I’d love is a role which allows me span boundaries: as someone who understands technology, can code, can architect, knows how to align business with business structure and technology architecture; as someone who knows the importance of knowing what is being build will meet customer needs.

If you know of such a role I can always be tempted, until then, I’ll stick to consulting.

My last entry I discussed some of the lessons I learned coding the Agile on the Beach submission and review system, Mimas (feel free to have a play). For completeness I’d like to tell you what the system does and what I want to do next for the system:

For the speaker….

What you get is a fairly basic form to submit a proposal. You receive an e-mail confirmation and at some later date notification of the outcome. You should also receive a link to the scoring and comments your submission received - that is, if the organiser wants to send it.

Before I go on, it is worth pointing out that Mimas is build around the assumption that conferences have tracks, e.g. software coding track, product design track, etc. Submissions are tied to a conference track, reviewers are asked to review all track submissions and final decisions are made on a track-by-track basis. Since tracks are configured when the conference is set up they are largely fixed. That could change in future but right now they are fixed.

For the reviewer…

Reviewers are assigned to one or more tracks and asked to review the submissions in the track. They get a list of all the submissions and for each one can score the submissions from -3 (don’t want) to +3 (really want.) That is round one. The conference organisers can then decide which submissions to shortlist for round two.

In round two reviewers are asked to rank the shortlisted submissions - from 1 at the top to… well however many are shortlisted, 5, 6, 10, 16 - whatever.

For organisers….

Creating a conference goes without saying! - They can configure it too: maximum number of submissions per speaker, max number of co-speakers, tracks, talk types and durations, expenses options, e-mail templates, e-mail ccs & bccs and a few other bits.

But all organisers are not equal. There is a permissions system which allows the conference creator can decide just what other organisers are allowed to see and do. They also get to decide who the reviewers are and assign them to tracks.

Most of what the organisers see are reports which slice and dice the submissions in different ways but those with the correct permissions can do some other things:

What happens next?

There are two “big” changes I’d like to make…

I want to revise the way the system handles review so that rounds become configurable. Right now there are two rounds of reviews: one a scoring system, -3 to +3 and a second ranking round. I want to allow conference organisers to decide how many rounds of voting there should be and select the type of round they want. That will allow me to configure scoring (e.g. 0 to 5 instead of -3 to +3), add some more types of voting (e.g. multi-criteria), configure rounds and allow speakers to be anonymised.

The other big change, which comes from reviewer feedback, is to allow private comments. At the movement all reviewer comments on submissions are shared with submitters. But reviewers want the ability to make comments that are not shared.

This is a difficult one, I’d like reviewers to be open and share all their thoughts but some reviewers don’t like that. And because of that they find the system less useful. If I was Apple maybe I’d just say No, thats the way it is. But I’m not Apple and I need to meet client expectations.

Technically, I want to change the e-mail handling system, again. Although this is in its third version I’ve seen better ways of doing it. This is classic refactoring, each time I’ve change the way the e-mail system works I’ve seen a better way of doing it. Submitters and reviewers won’t see much change but improving the architecture will allow me to make enhancements more easily in future.

The other technical change I should make concerns testing. I really should look at ways to bring more of the UI under test - or at least run “bigger” tests. While there are lots of fine grained unit tests increasingly I find it necessary to manually test how the system hangs together, e.g. when I make changes to mail handling. This is because actions happen in the UI which cause quite a lot of stuff to happen below.

There are many more small changes I want to make to the system but they would probably take longer to describe than to write about!

So the last question is: is this worth while?

If the system is only ever for Agile on the Beach then probably not. It works.

If the system is used by other conferences then some of these changes, perhaps all, are worth doing. But then, maybe until I make those changes none will use it!

A classic dilemma.

If the system is my own little play thing then yes, all these changes are worth doing because I enjoy coding it! But enjoying doing something is different from it being commercially worth while. Financially I’m certainly better off doing something else. But if I value a hobby then it is worth doing.

Another classic dilemma.

One might ask: has it been worth doing so far?

Improved the AOTB submission and review process: Definitely!

Refreshed my programming: Yes

My own personal learnings: Yes

Created an option for others: Yes

Financial returns? No

Its just a shame that the first four don’t pay the bills!

Another classic problem.

The picture above is the documentation for Mimas, the conference submission and review system I wrote for Agile on the Beach. The documentation is three A4 sheets (2 state diagrams and one short paragraph of an assumption) plus an A3 object model - actually the database object model. All stuck to the wall in my office.

That is all the paper documentation, there are over 100 unit tests too which form pretty good documentation and have allowed me to continue changing the live system. There is also a physical stack of cards on my desk which form the backlog, although the most important changes I need to make are firmly logged in my brain.

A couple of my blogs have mentioned Mimas before but in this entry I just wanted to share some lessons about the system and my first serious programming effort in years.

For the record the system runs on the Google AppEngine, it uses standard Python AppEngine libraries, e.g. webapp2 plus a light coating of BootStrap on the UI - thanks to Sander Hoogendoom for that suggestion - and SendGrid for mail but apart from that is pretty much free of libraries. It comprises 8500 lines of Python including 3300 lines of test code. There are another 2400 lines of HTML which contains about a hundred lines of JavaScript. The JavaScript gave me an interesting insight…

I like to think I know Python but I don’t think I know JavaScript, the JavaScript I used here was 50% scrapheap challenge and 50% programming. On the few occasions I did anything more than a simple function I found I spent an inordinate amount of time getting it to work. I kept putting this down to not really knowing JavaScript - plus perhaps being a bit snobby about JavaScript not being “real” language.

But, fairly late in the process I realised why JavaScript took so much time and why Python was so fast: The Tests.

The Python was properly Unit Tested. When I needed new functionality in the server end I built it test first. And it just worked. Time and time again I surprised myself how quickly I got things working.

Not so in JavaScript, I kept avoiding it and when I did something it just took too long which made me dislike JavaScript all the more.

But… when I came to UI I’d let myself off about the unit tests. I never set up a test framework. And so I never unit tested my JavaScript either. I slowly, lately, realised a lot of my JavaScript mistakes would never have happened if I had unit tested it. And I’d also wager my UI development generally would have been faster if I had properly unit tested it. UI tests take longer, manual tests take longer, it takes longer to find out something doesn’t work and to try something else. Fail fast, fail cheap.

Lesson 1: Be even more honest with unit testing.

Lesson 2: Yes unit testing the UI is more difficult but that shouldn’t be an excuse for not trying.

To some degree I would defend myself by saying I was really new to JS and a lot of the webapp2 UI ideas and was just learning. But that begs the question: would I have learned faster with tests? At some point, before today, I think I would have done.

Although I didn’t unit test the front end I did keep a strict front-back division and pushed as much logic as I could not the back.

Lesson 3: I was already (subconsciously?) compensating for where I knew I was weak.

(By the way, Python support for mocking and stubbing is good but can someone in the Python community please document it properly? Its still a bit of magic too me.)

One of the reasons I avoided third party libraries was because of the time it took to get them working. Take dragular - for example, it is a JS drag and drop library which claims to be “so easy it hurts the brain.” I couldn’t get it to work.

I spent a couple of days with it. (I could really do with drag and drop in one part of the system).

Then I gave up and in a day knocked together a non-drag and drop alternative - not as good but it works.

Lesson 4: Even ready to use code libraries have learning curves, sometimes that learning curve is longer than doing it a different way. The cost of reuse.

Something else I relearned: those really trivial bits, the bits you easily convince yourself you don’t need to test? Like getters and setters.

Well, if you do the tests you may well find they were so trivial you didn’t pay attention and got them wrong.

Lesson 5: Unit testing the most trivial stuff can actually be the most valuable.

I say I relearned this because I learned it with a previous development a year or two back and comparing notes with James Lewis found he’d had a similar experience!

In general I’m impressed by the Google App Engine. There are some places I got stuck and a couple of things which just don’t seem to work or are not really good enough (__init__ constructors and NDB come to mind.)

Mail handling caused me a lot of problems. In some ways I can’t blame Google for this ‘cos their documents discourage you from using their own mail handling system. When I eventually did cut across to SendGrid not only was the change far easier than I expected but it also solved some other issues I had.

Lesson 6: Sometimes we resist changes which are actually good for us.

Live running the system caused surprisingly few problems. The only real problem we had in live was hitting a Google quota limit. It turned out this was a quota limit around mail sending and was eventually force the move to SendGrid.

But… The Google docs on quota limited a far from clear. Or rather, the Google diagnostics are far from clear. The logs told me I’d blown a quota but not which one. It took a lot of hunting, and some guesswork, to find it was mail - not the number of mail messages but the frequency. Even then I got it wrong because the Google quota allowances have changed over time, not only is a lot of old information still on the web but some of the limits aren’t clear or seem to contradict one another.

Lesson 7: Select may not be broken but sometimes it hard to know exactly what isn’t working.

Overall, I managed again to prove Hofstadter's law but in part that was because I enjoyed myself so much! Really, I’d forgotten how much fun coding, and seeing the code work, is. Quite possibly, I spent too much time coding last year and not enough doing paid work.

And perhaps, this is what non-coders don’t like about coders. They see programmers enjoying their work and they fear the programmers are doing more because they are enjoying themselves. And maybe, they are right. But that isn’t a reason to make programming miserable!

In the first few weeks of coding I kept a very sharp focus on “Only what do we need for Agile on the Beach” but at some point I let myself go and enabled it for other conferences. But at that point I actually found it easy to change the system because it had been built well and built with tests.

Lesson 8: It is really hard to keep a focus on just what you need for now

Lesson 9: If you focus on good engineering broadening it out will come naturally; if you focus on broadening it out you’ll forget the good engineering.

This made me wonder if I could work as a programmer again. I can still program but I’m under no illusions: I’d never get past the CV filtering let alone an interview. Firstly nobody would hire me because I haven’t commercially programmed for over ten years. But, more importantly I don’t have the libraries or other related technologies.

To pick a Python job at random, here is the one that came up first just now on JobServe:

+ Exceptional Python knowledge/experience

No, I’m not an exceptional Python programmer

+ Java, C/C++

My Java is very very rusty, my C++ just rusty but worse, I’m a C++98/2003 guy, I’ve no idea whats in 11 let alone 14.

+ Flask and/or Django

None

+ Agile, TDD, CI/CD

I’m rumoured to know a little about Agile, and a tiny bit about TDD but CI or CD… never really done it.

Fantasy over.

Lesson 10: Middle age ex-progammers may try to recapture their youth in code.

In my next entry I’ll say a thing or two about what Mimas does, but try it yourself. I’ve also set up a little site to publicise it - ConfReview.com.